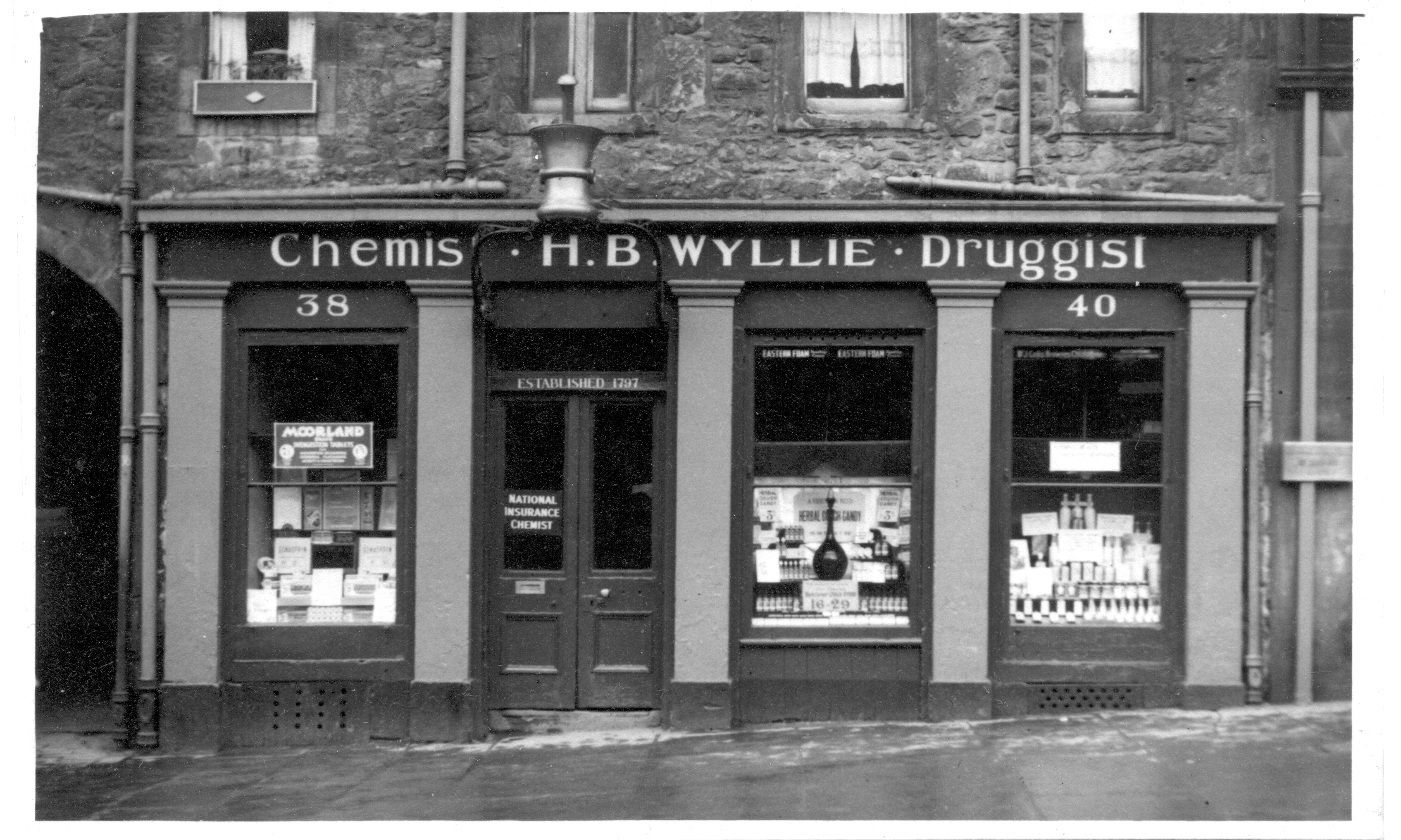

The rise of the Chemists and Druggists

A new pharmacy trade emerged in the eighteenth century, as the industrial revolution began.

The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries had left a gap in the market by moving into the role of general practitioner, and new chemists and druggists began to spring up in urban areas. They would typically own premises on the high street, where they mixed and dispensed chemicals and medicines, as well as selling tobacco, alcohol, cosmetics and food.

Unlike the apothecaries, the chemists and druggists were entirely unregulated, and without a national body to represent them, there was little sense of a pharmacy profession.

It was a competitive market, and chemists and druggists focused on the demands of their customers. Many specialised in different products, from chemicals for photography to developing matches - the famous Worcestershire Sauce of John Lea (1791-1882) and William Perrin (1793-1867) become so popular they gave up pharmacy to focus on its production.

In 1815, the introduction of the Apothecaries Act would have required all practicing apothecaries to hold a licence, so that the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries could control the chemists and druggists. The Bill required them to either become an apothecary or cease trading in medicines, but the chemists and druggists campaigned against the Bill and won.

However, this campaign had made it clear that the new chemists and druggists needed to protect their interests by joining together.