Section 3: Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

Burnout is defined as a ‘psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job’ (Maslash, 2016). In this survey burnout was measured using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti, 2010), a 16-item questionnaire which measures burnout through two factors; emotional exhaustion and disengagement in relation to work.

Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with 16 statements using a four-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree (see Appendix 2). Every item is scored, and item ratings averaged into a single index (1-4) where a higher score is indicative of increased burnout.

Risk of burnout varies by profession and a lack of consistency in the tools used to measure burnout creates challenges when trying to establish benchmarks. In this report, a score of equal to, or greater than, 2.25 for exhaustion and 2.1 for disengagement was used to identify respondents at ‘high risk’ of burnout based on their responses (Peterson, 2008).

The 2020 findings suggest that 89% of all respondents were at high risk of burnout, scoring above the defined cut-offs for exhaustion and disengagement. Further analysis was undertaken to explore whether there were any differences between different groups of respondents, for example, the risk of burnout appears to be highest for those working in community pharmacy (at 96%) and provisionally registered pharmacists (at 95%), and a slight increase in the risk of burnout was also observed in those respondents at an earlier career stage.

In addition, a higher number of BAME respondents were at risk of burnout (95%) compared with 87% of white respondents. These differences, however, should be interpreted with caution given the small samples sizes involved.

Research has shown that risk of burnout in healthcare professionals has wider implications on the delivery of care, risk of medical errors, sick leave and general workforce retention (Durham, 2018; Elbeddini, 2020; West, 2018).

Analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between risk of burnout and the responses to a series of questions on work enjoyment, quality of service offered, concerns about making mistakes at work, time taken off work due to sick leave and general retention. The findings of each question are also explored in more detail below.

3.1 Enjoyment of work

A range of responses were received when respondents were asked to rate their enjoyment of work on a scale from ‘I really enjoy my work’ to ‘I really don’t enjoy my work’, with the majority of respondents sitting on the more positive end of the scale. Over half of respondents (55%) stated that they either enjoyed or really enjoyed their work, compared with a third (27%) who did not enjoy, or really did not enjoy their work (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Rating of work enjoyment on a 5-point scale best reflecting the respondents on a day-to-day basis.

There was an almost 20% difference in the risk of burnout between respondents who enjoyed or really enjoyed their work (80% at risk of burnout), and respondents who didn’t enjoy or really didn’t enjoy their work (100% at risk of burnout), suggesting that there is a relationship between risk of burnout and lack of work enjoyment.

Other studies have shown a correlation between job satisfaction and burnout, generally, suggesting that lack of job satisfaction is associated with exhaustion and high risk of burnout (Demerouti, 2010; Piko, 2006).

3.2 Concerns around service quality and making mistakes at work

Respondents were asked how frequently they worried about the impact of their mental health and wellbeing on the quality of service they provided. This was followed by a question on how frequently they worried about making mistakes due to the impact of work on their mental health and wellbeing. The responses for both questions tended to fall in the middle of the scale, between often and occasionally (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Responses to the question asking how frequently respondents worried about the quality of service they offered and making mistakes in their work, due to the impact of work on their mental health and wellbeing.

A higher number of respondents working in community practice selected that they always worried about making mistakes when compared to those who worked in hospital or general practice. Moreover, only 8% of those working in community stated that they never worried about making mistakes at work, which was the lowest compared to all the other sectors.

Not unexpectedly, respondents with less practice experience appeared more likely to worry about making mistakes at work compared to those with more practice experience. For example, 21% of respondents with 3-10 years’ experience reported that they always worried about making mistakes compared to only 8% of respondents with over 21 years of experience.

Further analysis of the responses revealed that 99% of all respondents who selected that they always worried about making mistakes in their work were at high risk of burnout, compared to 62% of respondents who selected never. While this was only a frequent concern for a small number of respondents, existing evidence on the association between poor mental health, burnout and the risk of errors occurring, highlights the importance of good mental health and wellbeing to ensure service quality and avoid medication errors in the workplace (West, 2009).

It is important to note that these findings only convey respondents’ personal concerns and are not indicative of actual mistakes having been made. Further research would be needed to understand if these concerns were reflected in error reporting.

3.3 Time off work (sick leave)

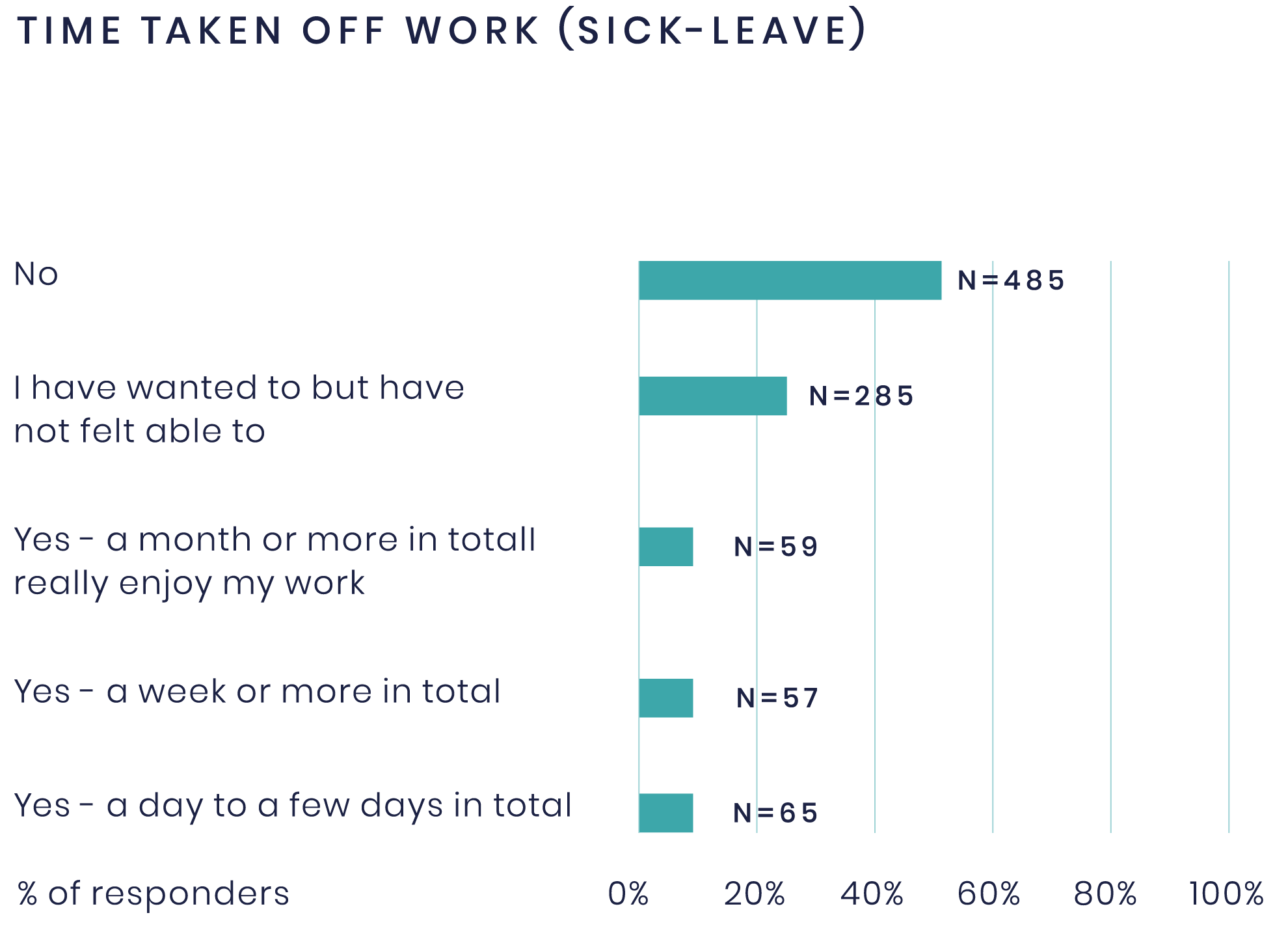

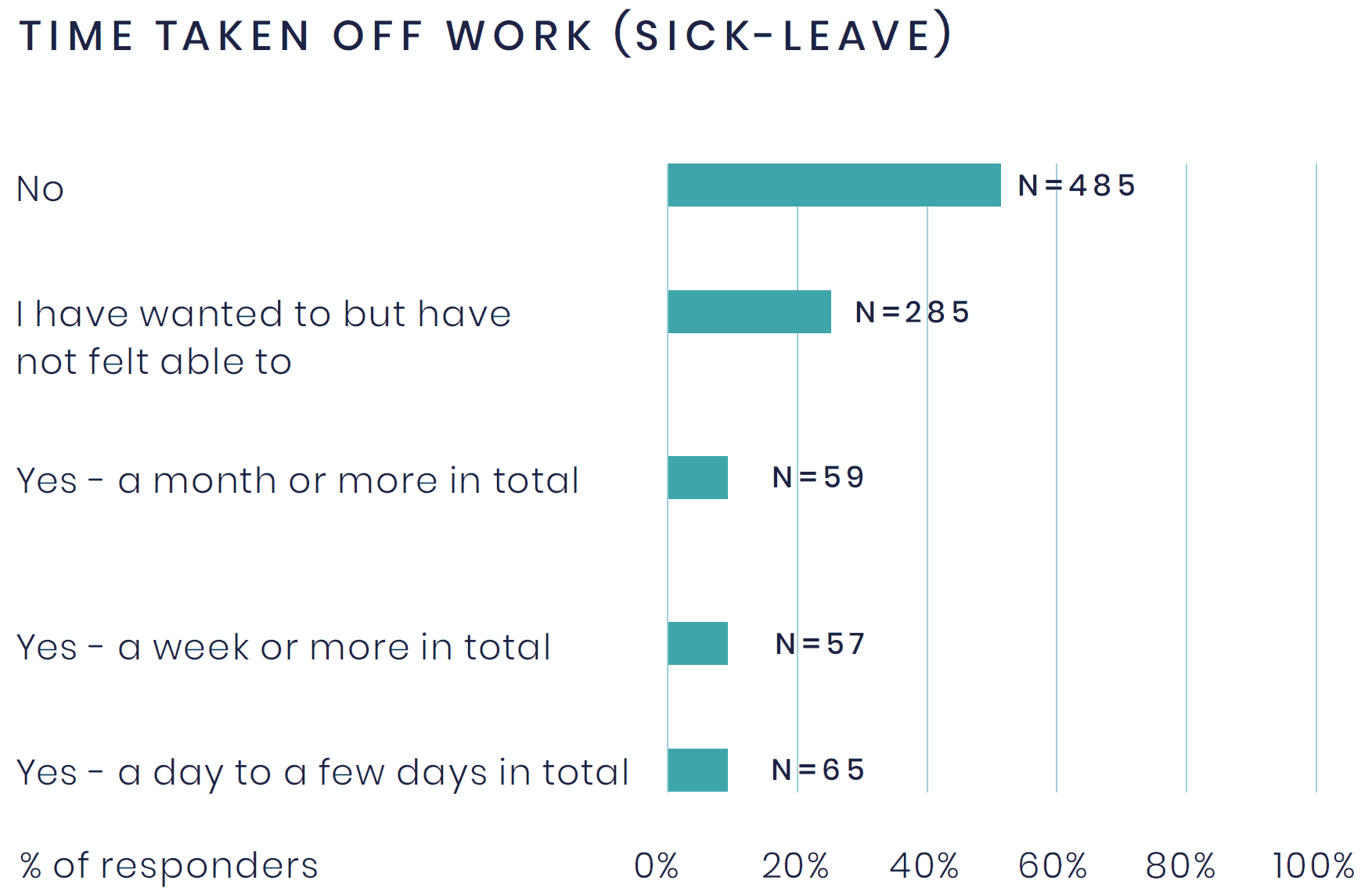

The majority of respondents (51%) had not taken any time off work for sick leave in the last year. A fifth (19%) of respondents had taken between a day and a month or more of sick leave (sum of all yes answer options) in the last year (see Figure 6). Furthermore, almost all the respondents who had taken time off work were at high risk of burnout (98%). Comparatively, 80% of those who had never taken any time off work for sick leave were at high risk of burnout.

A relationship can also be established between respondents who found work to negatively impact their mental health and wellbeing and the frequency of sick leave. For example, 23% of respondents who stated that work had a negative impact on their mental health and wellbeing (n=690) had taken between a day and a month or more of sick leave in the last year. This compares to only 6% in respondents who had selected that work had a positive impact on their mental health and wellbeing (n=94).

Figure 6: Time taken off work (due to sick leave) for all respondents. The analysis considers the sum of all yes categories, reported as ‘a day to a month or more’ off work in total.

In addition, one-third of respondents reported that they had wanted to take time off work for sick leave but had not felt able to do so (see Figure 6). Almost all these respondents (99%) were at high risk of burnout. The reasons for this were not explored in this survey, however findings from the British Medical Association (2020) suggest that the stigma around mental health often acts as a barrier, preventing people from accepting support, or asking for time off.

Similarly, the Boorman review (2009) identified that the current management practices and behaviours of many workplaces are “ incompatible with the delivery of high-quality health and wellbeing services for staff”. This aligns with findings from the 2019 RPS Mental Health and Wellbeing Survey which highlighted that the workplace culture in pharmacy was not conducive to good mental health and wellbeing.

3.4 Respondents who have considered leaving their job or the profession

Responses received to the question on whether respondents had considered leaving their job or the profession (due to the impact of work on their mental health and wellbeing) are presented below.

- 33% of respondents stated that they had considered leaving their current job.

- 34% of respondents stated that they had considered leaving the pharmacy profession.

- 28% of respondents stated that they had not considered either option.

Retention appears to be a bigger issue in some sectors compared to others, for example, a larger number of respondents working in community (47%) and general practice (49%) stated they had considered leaving the profession, in comparison to 27% of those working in hospital.

It is interesting to note that data collected by the GPhC found that 82% of pharmacists planned to renew their registration in 2019 while 16% of the profession were undecided and 2% did not plan to renew (Eventure, 2019). While direct comparisons cannot be made with this data, our findings suggest that the number of respondents who had considered leaving the profession has increased. However, there is clearly a distinction between considering leaving the profession and the intent to not renew registration.

Further research would be required to understand if there has been an increase in the number of individuals planning to leave the profession.

Reasons for leaving the profession were not explored in this survey, however, the GPhC found that reasons for not renewing registration included low job satisfaction, low morale, pay, workload, pressure, dislike for the pharmacy profession and a lack of respect, recognition and support from employers (Eventure, 2019).

In summary, the risk of burnout among respondents is high and appears to be linked to a lack of work enjoyment, frequency of sick leave, concerns around service quality and making mistakes at work, and workforce retention. The findings suggest that the culture of many workplaces is not conducive to positive mental health and wellbeing and that this is having a detrimental impact on the profession.